Blessed Are the Peacemakers: A Biblical Theology of Human Violence. By Helen Paynter. Grand Rapids: Zondervan Academic, 2023. 352 pages.

Helen Paynter’s Blessed Are the Peacemakers draws together her years of focused study on how the Bible may impact violence in personal relationships, societal structures, and warfare between nations. Though she works with people from a diversity of faiths in her peace-making efforts, her scholarship is from a distinctively Christian perspective. Paynter thus models how one may serve from a place of deep conviction to build a safe and peaceful community with those who are of very divergent perspectives. She holds numerous roles at Bristol Bible College, including Executive Director of the Centre for the Study of Bible and Violence. Her academic work is consistently cojoined with praxis to engage the Christian churches around the world for the sake of peace and protection of the vulnerable. Chaplains serve in a similar context as they hold firmly to their faith while caring for others from a variety of backgrounds.

Dr. Paynter is the right person to author such a work. Violence is not just about warfare, and her previous publications (both scholarly and practical) range among topics as diverse as hospitality, immigration, sexual assault in churches, and include studies on violence in biblical narratives. She has long been in conversation with other scholars on these topics and in Blessed are the Peacemakers invites readers to join in as these conversations are brought together into one place. Years spent pondering these topics also rewards the reader with wonderful additional treasures along the way, such as her reference to Karl Jenkin’s choral work, “The Armed Man,” numerous, relevant news stories, and personal encounters.

The book is part of Zondervan’s “Biblical Theology for Life” series, which uses a hermeneutic that explores biblical theological themes to answer to real-world questions in ways that matter for today. The series covers topics as divergent as personal identity, the natural world, stewardship, and human violence. Together, these books model a way to explore the Bible in conversation with contextual and contemporary voices that can direct and empower a relevant and lived faith. Paynter’s work follows the format of the series and divides into three sections: “Queuing the Questions” raises the issues the author seeks to address; “Arriving at Answers” develops a biblical theology that responds to the issues raised and seeks to answer the initial questions; the final section, “Reflecting on Relevance” traces ways that biblical theology applies to a variety of contemporary settings and may be lived by people of faith in the world today.

Paynter sets the stage for the discussion in “Queuing the Questions” by defining human violence as “the use of force or coercion in a way that causes harm to another.”[1] Her definition is broad enough to cover topics of warfare, domestic abuse, societal inequalities, and the treatment of inmates. Her discussion is also specifically limited to human violence against another, so issues of theodicy and self-harm are not addressed. To frame her work, she raises key questions: 1) What drives human violence? 2) Does the Bible contribute to the problem of violence? and 3) Is the Christian faith inherently violent?

In “Arriving at Answers,” Paynter develops her biblical theology relating to human violence. She first shows that the Bible testifies to a peaceful creation, without inherent violence. The fall brings discord between humans and an ensuing violence. She then investigates violence in warfare where ancient Israel was more restrained than its neighbors and then in peacetime both interpersonally and structurally, where the Torah sought to restrain violence perpetrated in Israel. She next explores violence as portrayed in the Bible from the victim’s side, looking at voices of grief and protest as well as forms of resistance.

At the heart of her biblical theology are redemptive trajectories she sees evident before and culminating at the cross, including the de-valorization of violence, the invalidation of vengeance, and the emergence of the innocent victim. These trajectories are a counter-testimony to the violence found in Scripture and are an emerging response to the warfare and structural violence exhibited within the narratives. In her discussion of eschatology, she notably concludes that human violence has no part in the eschaton, undermining the argument of any who would misuse such texts to justify violence in the here and now. She also notes that the rhetoric in Revelation undermines divine militancy, e.g., victory belongs to the slain lamb and the sword is from his mouth rather than in his hands. Her discussion of “living the new reality” evaluates two test cases of military service and slavery in the New Testament and the early church. Both cases reveal a movement towards an ethic of peace undermining the existing structural violence. However, these were only the first steps as the Christians discovered how to live their faith in a morally ambiguous world. Christians have continued this journey of discovery for the last two millennia.

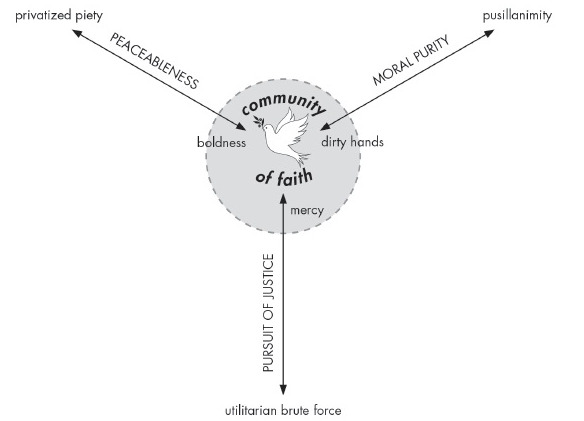

The most original contribution of Blessed Are the Peacemakers comes in the third section, “Reflecting on Relevance.” Her chapter, “Towards a Praxis,” is the heart of this effort, where she lays out a model for how Christians should respond to violence. She identifies three eschatological goals: Peace, Holiness, and Justice. These goals call Christians to live out three virtues of peaceableness, moral purity, and pursuit of justice. The virtues she identifies tend to pull against each other in ethical decision making, and each (in their extreme) has an inherent danger leading to inaction or overreaction. Tempering these virtues (peaceableness with boldness, moral purity with dirty hands, and justice with mercy) allows for responses that are closely aligned with all three virtues. She invites communities of faith to respond to violence not with prescribed reactions but rather with a circumscribed range of ethical responses within which improvisation leads to a faithful response. For Paynter, improvisation keeps one’s action in line with the biblical narrative and acknowledges unique applications in an ever-changing, broken world. She summarizes this in a diagram (figure 1.) which is quite helpful for understanding her model.[2]

The closing seven chapters are Paynter’s application of lessons learned to the contemporary context. Her first priorities are the church’s internal and external responsibilities of peacemaking. She then addresses responses to several different issues related to violence: warfare, gun control, capital punishment, and the treatment of immigrants. Her discussion of each topic clearly comes from many years of study and writing on these issues. Paynter evaluates arguments from competing positions on an issue and then offers contributions to strengthen one of the positions for the church’s response. Unfortunately, in many cases, she seems to come to what she earlier refers to as a single-point, ethical “sweet spot,”[3] as she addresses each of the issues. For example, using arguments familiar to the ongoing debates, Paynter concludes capital punishment has “no place in civilized society.”[4] In her discussion on gun control in the U.S., “the current availability and use of guns is . . . a ‘grievous injustice.’”[5] Whether one agrees with her conclusions, it would have been helpful if Paynter had used her own matrix to facilitate these discussions. Such an effort would have led to a proposed, circumscribed range of responses within which faithful improvisation is possible. Paynter would have landed in a much more novel place had she clearly applied her own framework when working through particular cases.

Two final comments are due before turning to the specific audience of chaplains. First, the Biblical Theology for Life series editor made an unfortunate decision to forego bibliographies. This is a loss for attentive readers who want to capture references for future study as they read. Second, her work engages in many of the scholarly conversations about the Bible and violence over the last 35 years. For readers particularly interested in the subject of warfare in the Bible, William Webb and Gorden Oeste’s Bloody, Brutal, and Barbaric? is more directly focused on this specific topic and is worth reading in tandem as Paynter’s discussion applies their conclusions in key places.[6]

Readers may be particularly drawn to her discussions of violence in wartime (ch. 5); military service in the early church (ch. 11); and views of war (ch. 14), though one may disagree with her conclusions. However, do not miss the greater value of this book. It exemplifies how adherents of any religious tradition may address a diversity of violent issues with and from within their sacred texts. Chaplains may, at times, feel a (false) dichotomy between deployed ministry and that done at home station. Paynter’s work boldly reminds us that our confessional positions are the singular remedy we bring to whatever violent issues the U.S. Army faces. The religious support chaplains provide is regularly tied to human violence—obviously in combat, but also when ministering at home station amid sexual violence, equal opportunity concerns, as well as when addressing counterproductive leadership. Paynter’s approach reminds us that theological integration is essential for our ministry and empowers us to address the consistent hurts that violence brings in our broken world.

Paynter, Blessed are the Peacemakers, 27.

Adapted from Paynter, Blessed are the Peacemakers, 239.

Paynter, Blessed are the Peacemakers, 238.

Paynter, Blessed are the Peacemakers, 291.

Paynter, Blessed are the Peacemakers, 286.

William J. Webb and Gordon K. Oeste, Bloody, Brutal, and Barbaric?: Wrestling with Troubling War Texts (Downer’s Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2019).