From June to December 1942, the United States Army War Show toured 18 cities in the eastern half of the country, reaching an audience of over 4 million civilians.[1] This traveling spectacle celebrated the nine branches of the Army, demonstrating innovative tactics and technology through a two-hour performance and interactive booths. A product of the War Department’s Bureau of Public Relations, the War Show hoped to inspire awe and patriotism while reassuring the American public of the military’s efficiency, organization, and training. Proceeds from the War Show’s ticket sales went to the Army Emergency Relief Fund, further involving the civilian attendees with the war effort.

Amidst the exciting presentations of flame throwers and tanks in the War Show’s prepared program, a much quieter 4-minute vignette featured the Chaplain Corps. During this segment, a Jeep towed a small trailer into the arena, out of which two chaplains produced a fully-outfitted altar under a spotlight. In the Chaplain Corps’ exhibit booth, audience members could more closely view the trailer’s ecclesiastical equipment, which included a portable folding altar, portable pump organ, candlesticks, and other articles needed for religious services. As Irene M. Hawkins, the Women’s Editor for The Detroit Times, reported to her readers, this “church on wheels, a portable field chapel, [was] the most important display” from the Chaplain Corps for War Show attendees.[2] Its presence assured the American public the spiritual well-being of their servicemen was a priority overseen by the War Department.

As evidenced by the War Show’s emphasis on religious material culture (the tangible items used for religious services or personal devotion), by 1942 the Army Chaplain Corps was not just its chaplains, but also their gear. Chaplains relied on physical equipment to accomplish their duties; in turn, these objects represented the chaplain’s responsibilities and identity. At the center of a chaplain’s activities, especially on deployment, was their field equipment that often comprised of only a chaplain’s “kit:” a single suitcase designed to carry the most essential ritual objects for Catholic, Protestant, or Jewish services. The War Department did provide some of these kits to chaplains and proudly displayed them at the War Show’s exhibit, but Army chaplains largely depended on their home parishes, local congregations, or national religious organizations to secure necessary devotional objects and complete kits. By World War II, civilian efforts to furnish military chaplains with essential religious equipment was well-established.

Sourcing Spiritual Supplies

After the United States’ entry into World War I in April 1917, civilian organizations such as the Young Men’s Christian Association, Red Cross, Jewish Welfare Board, and Knights of Columbus regularly equipped U.S. military chaplains with Bibles, rosary beads, and Torahs to distribute to soldiers. The Senior Chaplain for the American Expeditionary Force (A.E.F.), headquartered in Europe, coordinated with these religious groups to obtain resources for U.S. chaplains, but as fighting continued, this became burdensome.[3] Despite this, by March 1918 the General War-Time Commission of the Churches advised all chaplains that, while some equipment was available in France, they could not expect to find “portable altars and communion services” or typewriters.[4] These items needed to be purchased in the United States prior to embarkation, and it was up to individual chaplains to bring their own objects for religious services.

Local charity and social clubs, congregations, and private donors gave money and altar supplies to be included in the chaplain kits. Proper ecclesiastical equipment was especially imperative for Catholic chaplains, who needed ritually consecrated altar stones, chalices, and holy oil to perform absolution and last rites for Catholic soldiers on the battlefield. Catholic citizens in the United States, led by the newly formed National Catholic War Council and the Chaplains’ Aid Association (C.A.A.), launched an unprecedented initiative to supply portable Mass kits to Catholic military chaplains serving in Europe.[5] By the time of the Armistice in November 1918, the C.A.A. had provided over 600 Mass kits to chaplains.

By World War II, the War Department’s Bureau of Chaplains attempted to assist with efforts to equip chaplains with basic items. The April 1941 Army Technical Manual allocated a large field desk, portable typewriter, chaplain’s flag, folding organ, and a set of Army and Navy Hymnals for each chaplain.[6] Chaplains’ kits, including a Jewish kit, were only available through special request. Army chaplains could apply for $40 to purchase any further religious equipment specific to their faith, but many waited long periods for approval and found the allotted funds too limited for their needs. In addition, any items purchased with the $40 were considered government property and not that of the chaplain himself.[7]

Despite the War Department’s efforts, in World War II most chaplains’ equipment still originated from civilian individuals and organizations who attempted to provide kits to chaplains by the time they entered the Army Chaplain School. Between January 1942 and February 1944, the C.A.A. provided “1,355 Mass kits, 250 Benediction sets, 552 sets of vestments, 233 albs, [and] 6,526 candles.”[8] Protestant denominations donated portable communion kits, mostly made by the National Church Goods Supply Company and International Silver, to Protestant chaplains as well. One of these chaplains was Edmund A. Bosch, whose communion kit was a gift of the King’s Daughters at the Holy Trinity Lutheran Church in Buffalo, New York.[9] Jewish chaplains’ kits also circulated and were utilized by rabbi chaplains.

Providing chaplains with devotional objects, however, was not enough. These items needed to be portable, not take up valuable space in military shipments, and durable in harsh field conditions. A post-World War II Army report recommended that the chaplain’s kit be made lighter in weight to allow for easier transport.[10] The practicality of field equipment was paramount to the success of a chaplain’s duties, but even with the correct religious items, the Army chaplain encountered another obstacle to his work: reliable transportation.

Transporting Chaplains

An Army chaplain’s duties necessitated constant movement, especially on deployment, but adequate transportation for chaplains and their gear was a perpetual issue throughout both World Wars. By 1918, a handful of Army chaplains in Europe had managed to borrow a horse or motorcycle with which to travel between assignments, while the majority often journeyed on foot for several miles a day. Chaplains frequently wrote to their home denominations about walking long distances, carrying their kit, to reach multiple regiments and casualty stations.

The lack of transportation, beyond inconvenience, interfered with the amount of materials that a chaplain could manage and therefore impacted his range of ministry. The 1st Division Chaplain of the A.E.F. noted in his September 1918 monthly report that the shortage of vehicles meant “the Catholic Chaplains cannot carry even a portable Altar. The Protestant Chaplains cannot have even song sheets. It is as tho [sic] the Medical Department were expected to do its work without drugs or surgical instruments.”[11] A month later, the Head Chaplain of the 5th Division echoed this sentiment, insisting “that MOTOR TRANSPORTATION [sic], preferably a Ford Truck, be furnished” for each regimental chaplain.[12] The employment of Ford trucks finally happened in early 1919, when the Jewish Welfare Board supplied all remaining Jewish Army chaplains with the vehicles, “making them the envy of all the chaplains in France.”[13]

Still, the itinerant Army chaplain remained a concern for the American public. Just prior to the United States’ entry into World War II, a series of exchanges in the weekly Catholic magazine, America, criticized the Army’s continued lack of transportation for chaplains. Beginning the dialogue in August 1941, an eye-witness description of the frenzied training activities in military camps included the fact that Catholic chaplains said Mass and heard confessions in the backs of trucks while on maneuvers.[14] A letter to America’s editor the following month, written by an Army veteran in reply to the August exposé, verified that chaplains always had to “beg someone for transportation,” rendering them the “Army’s number-one hitchhikers.”[15] In October 1941, an anonymous Army priest further confirmed to America’s readers that his supplies and transportation “depend on the whims of the Commanding Officer,” simply signing his letter “Tailboard Chaplain.”[16]

Thus, by December 1941, the association of vehicles with the Army chaplain’s ministry was solidified. Still, while the 1942 Army War Show, which started six months after the United States’ entry into World War II, presented the notion that every chaplain had a Jeep and fully-stocked trailer at his disposal, in reality the “truck-and-trailer arrangement” on display was only provided to each Division Chaplain. Responsibility for the transportation for rest of the Army’s chaplains fell to individual commanding officers, but most chaplains found this inefficient and inadequate to their needs.[17] The problem was somewhat alleviated by a February 1944 War Department circular, which authorized the exclusive use of certain vehicles by all chaplains.[18]

Equipping Religious Pluralism and Visualizing Virtue

The chaplain’s trailer in the Army War Show was painted with two identifying symbols, a Cross and a pair of tablets under a Star of David, indicating that the Army chaplaincy encompassed multiple faiths. Many scholars have demonstrated that the increasingly pluralistic nature of the U.S. military chaplaincy by World War II paralleled the growing identity of the U.S. as a nation of tripartite faith: Protestantism, Catholicism, and Judaism.[19] Indeed, in the Army Chaplain School, chaplain candidates studied daily with men outside of their own faith while being trained in the performance of fundamental Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish services.[20] Although some candidates did not care for this arrangement, most clergy found these encounters productive and stimulating.

As the U.S. military chaplaincy itself became more pluralistic, so too the objects in their service were expanded to include items needed by all three religions. The War Show proudly displayed Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish chaplains’ kits, reinforcing the tangible aspects of the religious pluralism. When describing the 1942 chapel exhibit, Irene Hawkins noted that “the [temporary] chapel is made so that it can be rearranged in a few minutes to serve the three major denominations.”[21] An article on Army chaplains in the September 1942 issue of Life also highlighted the efficient consideration for multiple faiths, informing readers that “the Government has built 600 regimental chapels, all equipped with mobile altars and pulpits which may be arranged to suit the Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish forms of worship.”[22]

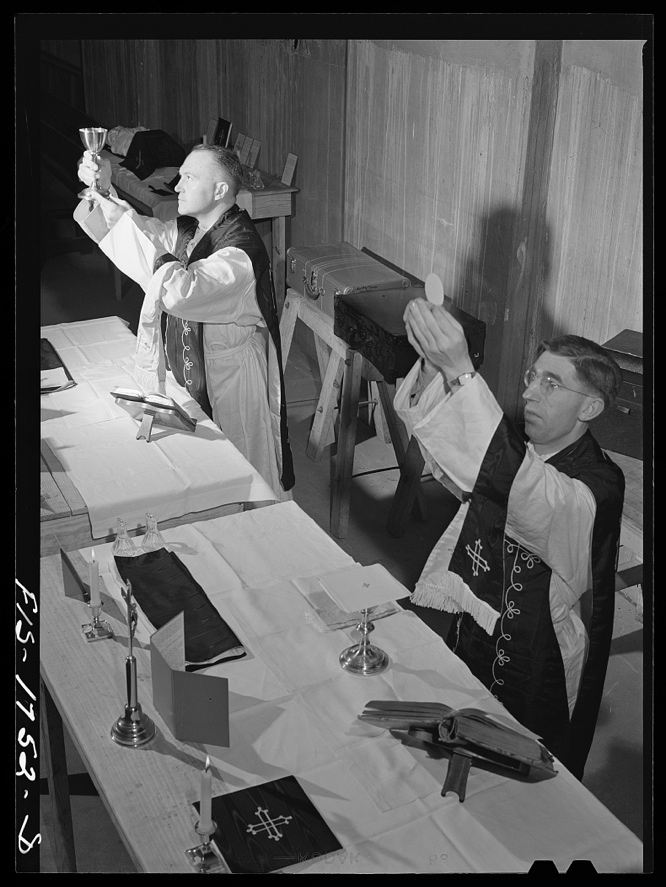

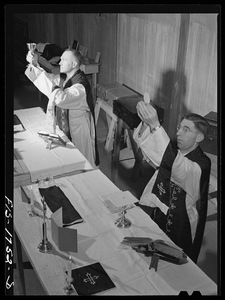

In April 1942, the visual association of an Army chaplain with his gear was furthered by Farm Security Administration photographer Jack Delano, who took a series of snapshots at the U.S. Army Chaplain School in Fort Benjamin Harrison, Indiana.[23] The photographs captured chaplains in their daily routine, learning tasks such as first aid, map reading, and graves registration. Among the images of chaplains practicing these skills are a handful of Catholic priests saying Mass, utilizing the items from their Mass kits. The kit suitcases for each chaplain sit behind them, illustrating that everything on the altar will be packed and portable. The Delano photographs emphasized training of chaplains not just in their Army duties, but also with the objects needed in the field.

As John C. Seitz has shown, photographs of Army chaplains using their religious objects, published frequently in newspapers and magazines, demonstrated to the U.S. public that the Allied cause was righteous and the spiritual needs of their soldiers were met.[24] Images of religious services and chaplains, like the Army War Show’s exhibitions, reassured civilians of the presence of piety on the battlefield. At the same time, photographs and articles that showed chaplains performing services reinforced the notion that the military encouraged religious practice and expression. At the center of these images of spiritual activities were the physical religious equipment, which defined the chaplain’s identity in the conflict.

Conclusion

The chaplain’s kit often became an item of personal significance to the chaplain, signifying his connection to his faith and his military flock. Father Joseph McCaffrey received a Catholic Mass kit in March 1918 and by October of the same year wrote that “it is by far the most precious article in my possession.”[25] Father Martin Fahy described his kit as “a valuable companion” that journeyed with him across Europe and kept him company.[26] Many chaplains who served in World War I, including Naval chaplain William Augustus Maguire,[27] kept their Mass kits after the conflict and even used them in World War II as well.

The lengths to which chaplains went to maintain their kits testifies to the personal and communal value of the equipment beyond practical use. In September 1918, Father Peter Leo Johnson wrote to his parents, lamenting he had been separated from his chaplain’s kit when his regiment suddenly moved. Once he found it again, he vowed “never [sic] to let it get away from me again.”[28] When chaplain Francis L. Sampson parachuted into Normandy on D-Day, he became separated from his Catholic Mass kit that sank into a river. Sampson dove into the river five times to retrieve it before reuniting with his unit.[29] In January 1945, Army chaplain Clarence A. Vincent reported that during a particularly intense German counterattack, he lost everything except the clothes on his back and his camera. A few days later, he successfully returned to the same location, still under enemy fire, to rescue his chaplain’s kit.[30] The items were so important that chaplains were willing to take great risks to retrieve them.

The 1942 Army War Show framed the material culture of devotion as a necessary part of warfare, integral to the success of the U.S. military. As Irene Hawkins remarked to her readers, “as the army travels so does the field chapel and chaplain.”[31] Yet while the War Show assured the American public that their chaplains were outfitted properly, the War Department was not the main resource for field equipment for chaplains in either World War. The reality of obtaining and transporting devotional items, especially in fighting sectors, was not always guaranteed and relied on civilian organizations and donors. At the center of discussions about chaplains’ objects in the World Wars were issues of portability, civilian reassurance and involvement, and material culture of religion. By 1942, the Army chaplain was not just a man; his role in the military was defined by the equipment in his possession and his chapel on wheels.

Susan Thompson, “Army War Show – 1942,” U.S. Army (August 2, 2023).

Irene M. Hawkins, “Church on Wheels, Part of War Show Exhibit,” Detroit Evening Times (July 31, 1942), 12.

Michael E. Shay, Sky Pilots: The Yankee Division Chaplains in World War I (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2014), 4.

General War-Time Commission of the Churches, Army Chaplains’ Information Bulletin (March 21, 1918), Folder 35, Box 15, National Catholic War Council Series 2: Executive Secretary, Archives of the Catholic University of America, Washington, DC.

For more on the CAA and Mass kits, see Sarah C. Luginbill, “The Eucharist in a Suitcase: The Chaplains’ Aid Association and Catholic Material Culture in World War I,” American Catholic Studies 136, no. 2 (2025): 25-42. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/acs.2025.a964330.

United States War Department, Technical Manual No. 16-205: The Chaplain (Washington, DC, April 21, 1941), 15-16.

This program, known as the Chief of Chaplains’ Religious Fund, started in 1940 and ended in 1944 (Roy J. Honeywell, Chaplains of the United States Army (Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Chaplains, 1958), 261-262).

Stephen B. Earley, “Prayers of Civilians Must Help Chaplains and Service Men,” America 70:19 (February 12, 1944), 512.

The kit is housed in the United States Army Chaplain Corps Museum at Fort Jackson, South Carolina. I am grateful to Marcia G. McManus for allowing me to access the kit and see the engraved donation label inside.

United States Army, Report of the General Board, United States Forces, European Theater: The Army Chaplain in the European Theater of Operations (Washington, DC, 1946), 105.

Monthly Report of the 1st Division Chaplain, September 28, 1918, Folder 1, Box 3820, Records of the American Expeditionary Forces (World War I), Record Group 120, National Archives at College Park.

Monthly Report of the 5th Division Chaplain, October 2, 1918, Folder 5, Box 3820, Records of the American Expeditionary Forces (World War I), Record Group 120, National Archives at College Park.

Lee J. Levinger, A Jewish Chaplain in France (New York: Macmillan, 1922), 61.

J. Gerard Mears, “The Chaplains Swing Along with the Lads in the Camps,” America 65:19 (August 16, 1941), 514.

W.H. Dodd, “Chaplains,” America 65:22 (September 6, 1941), 605.

Anonymous, “Chaplain’s Lot,” America 66:1 (October 11, 1941), 27.

United States Army, Report of the General Board, 104.

United States Army, Report of the General Board, 103.

See Jessica Cooperman, Making Judaism Safe for America: World War I and the Origins of Religious Pluralism (New York: New York University Press, 2018).

See Ronit Y. Stahl, Enlisting Faith: How the Military Chaplaincy Shaped Religion and State in Modern America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2017) and G. Kurt Piehler, A Religious History of the American GI in World War II (Omaha: University of Nebraska Press, 2021).

Hawkins, “Church on Wheels,” 12.

“Army Chaplain,” Life 13:11 (September 14, 1942), 89.

The school was relocated to Harvard University later that year.

See John C. Seitz, “Altars of Ammo: Catholic Materiality and the Visual Culture of World War II,” Material Religion 15:4 (2019): 401-432.

Joseph A. A. McCaffrey, untitled letter excerpt, Chaplains’ Aid Association Bulletin 2:2 (October 1918), 7, Box 106, NCWC, Series 9, Archives of the Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C.

Martin E. Fahy, untitled letter excerpt, Chaplains’ Aid Association Bulletin 2:4 (December 1918), 10, Box 106, NCWC, Series 9, Archives of the Catholic University of America, Washington, D.C.

Maguire obtained his kit prior to assignment as chaplain on the USS Maine, and continued to employ it after World War I, adding more vestments to it in the 1920s. See William A. Maguire, Rig for Church: The Thrilling Life Story of a Navy Chaplain (New York: Macmillan Company, 1942) and The Captain Wears a Cross (New York: Macmillan Company, 1943).

Peter Leo Johnson to his parents, September 8, 1918, 2, Box 3, Peter Leo Johnson Papers Collection, Archdiocese of Milwaukee Archives, Wisconsin.

Francis L. Sampson, Look Out Below! A Story of the Airborne by a Paratrooper Padre (Washington, D.C.: The Catholic University of America Press, 2023), 52.

Clarence A. Vincent to Grabowski, January 10, 1945, Box 2, Yank Club Collection, Redemptorist Archives of the Denver Province, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Hawkins, “Church on Wheels,” 12.

_and_lisle_bartholomew_(protestant)__with_their_assistant__al_s.jpg)

_and_lisle_bartholomew_(protestant)__with_their_assistant__al_s.jpg)